- Date

- 3rd February 2025

- Categories

- Gender

By Dr Rihab Khalid

Modern energy cooking services offer an opportunity to rethink the gendered division of labour in domestic spaces. Technologies like Electric Pressure Cookers (EPCs) have the potential to alleviate time and drudgery burdens, benefit women physically and socio-economically, and, perhaps most importantly, invite men into a shared responsibility for domestic work. Globally, women disproportionately bear the responsibility for cooking- preparing an average of 8 more meals per week than men in many countries in the global South. This imbalance arises from entrenched traditional gender roles and societal expectations. Modern cooking technologies can disrupt these gender norms, provided they are grounded in a feminist understanding of care work1, power dynamics2, and systemic inequities3. This blog explores how a feminist perspective on MECS is essential to promote gender equity within households and beyond.

Cooking as Gendered Labour: A Feminist Critique

Feminist analyses have long highlighted cooking as an aspect of unpaid reproductive labour, often undervalued within both societal and economic systems. According to the ‘devaluation perspective’, care work, including cooking, is marginalised because it is associated with the private sphere and women’s roles. This leads to its exclusion from policy discussions on energy access, infrastructure investments, and climate change solutions. Feminist scholars have critiqued the domestic kitchen as a site of women’s oppression, shaped by societal expectations of unpaid care work. Recent studies similarly emphasise that discussions around energy transitions often overlook women’s unpaid domestic labour, despite its significant contributions to household and community well-being.

However, more recent feminist scholarship has also reframed the kitchen as a space of potential agency and empowerment. Such studies argue that kitchens can become arenas for resistance and self-expression, particularly in contexts where women negotiate their identities and roles within extended kinship networks. Others have also highlighted how culinary practices and kitchen spaces have been reclaimed as spaces for empowerment, cultural expression, and political engagement. Similarly, ENERGIA’s work showcases how empowering women through clean cooking initiatives can reshape their roles in both domestic and public spheres, turning traditional spaces into sites of agency and change. This duality—kitchen as both a site of oppression and empowerment—underpins the feminist critique of cooking practices and their connection to energy systems.

The Role of Technology in Transforming Domestic Spaces

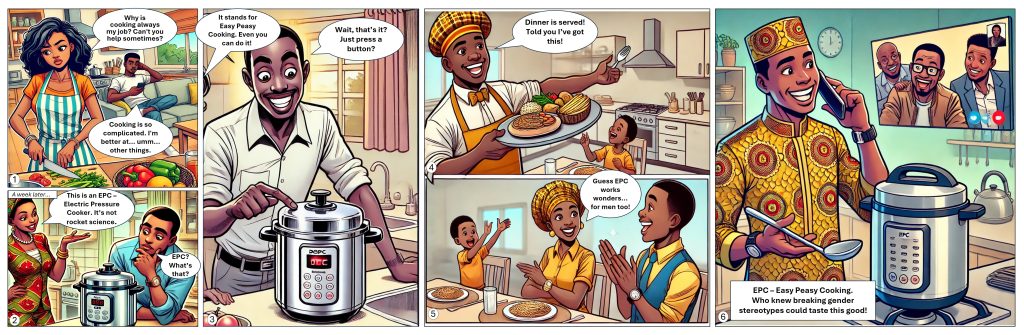

The comic strip above illustrates how modern energy cooking services like EPCs could potentially transform domestic spaces by inviting men into shared cooking responsibilities. By depicting a man confidently undertaking cooking duties, it challenges traditional gender norms and serves as a conversation starter about the potential for such change. While aspirational, this scenario underscores the need to explore how technology can catalyse shifts in deeply embedded social structures. Research shows that access to modern energy cooking technologies can save time, lower health risks, and even open opportunities for education and income generation. Yet, the key question remains: can technology break gender stereotypes and transform the gendered norms around cooking?

Technological interventions are not neutral. As Silva aptly notes, “gender is at work in the world of technologies.” The adoption and use of technology is deeply embedded in patriarchal norms. For example, studies in Malawi reveal that while women prefer electric appliances for their ease, financial decision-making often rests with men, who prioritise cheaper, labour-intensive options like charcoal. Similarly, others have shown that cooking initiatives often falter when they fail to consider the cultural significance of traditional cooking methods or the economic realities of low-income households. These challenges highlight how technology alone cannot dismantle entrenched social structures and may even reinforce societal inequities. MECS’ former research underscores this by showing how EPCs, often classified as non-productive resources by microfinance institutions, are deemed ineligible for loans. This exclusion unjustly undermines women’s domestic labour and limits their access to transformative technologies that could deliver both reproductive and productive benefits.

Feminist critiques caution against technological determinism—the belief that innovations alone can reshape social norms. Feminist scholars argue that systemic inequities—such as women’s limited agency in decision-making, economic precarity, and socio-cultural constraints—must be addressed alongside technological interventions. These systemic factors can hinder the transformative potential of technologies, particularly when program design excludes men or fails to engage both genders in challenging traditional roles. Instead, what is required is a nuanced approach that addresses the socio-cultural and economic contexts in which technologies are introduced. The comic strip aims to reflect this complexity, sparking reflection on how MECS might facilitate change when combined with broader systemic efforts to promote gender equity. By simplifying cooking processes, these technologies can challenge the notion that domestic work is inherently women’s responsibility, inviting men to share household tasks. When men adopt cooking responsibilities enabled by accessible technologies, it signals a meaningful shift in traditional gender roles and challenges societal norms that undervalue care work.

Towards a Feminist Clean Cooking Transition

A feminist approach to clean cooking transitions calls for systemic changes that centre care and prioritise equity, justice, and sustainability. This requires reframing cooking not just as a domestic chore but as a collectively shared and valued responsibility and a site of empowerment. It involves human-centred design, which focuses on co-creating technologies with women and other marginalised groups to ensure they align with users’ needs, preferences, and aspirations. It also includes redistributive policies that advocate for subsidies or free provision of MECS to low-income or female-headed households to ensure affordability and accessibility. Cultural transformation plays a role in disseminating knowledge and promoting educational campaigns that challenge gender norms and encourage shared domestic responsibilities- like the comic strip above. Finally, addressing structural change is essential for tackling the underlying socio-economic and cultural systems that perpetuate gender inequities, including through gender-sensitive and gender-responsive energy planning, urban development and public investments in cooking technologies and kitchen spaces. Moreover, it is essential that projects, interventions, and related marketing campaigns for the clean cooking transition exercise caution to avoid unintentionally reproducing or reinforcing traditional gender roles by over-emphasising women and undermining the role men can play in cooking and care work.

Modern energy cooking services are not just tools for cooking; they are catalysts for broader social change. When implemented with justice and equity at their core, they can contribute to a more inclusive and sustainable energy future.

Featured Graphic: AI-generated by the author, 2025.

***************************************************************************************************************

Notes:

1Care work is the unpaid labour associated with care giving and domestic responsibilities.

2Power dynamics are the imbalances in power such as in decision-making authority within households or access to financial resources.

3Systemic inequities can be understood as the long-standing societal structures that disadvantage certain groups based on gender, class, or ethnicity etc.