- Date

- 29th April 2019

- Categories

Dr Nigel Scott, Gamos

(Nigel is a Co-Investigator on the newly announced MECS programme)

I was at a meeting for the design challenge being organised by the Efficiency for Access programme by the Energy Savings Trust in London yesterday. E4A have already supported MECS by including efficient electric cooking in a challenge fund organised as part of their Low-Energy Inclusive Appliances (LEIA) research and innovation programme (money and technical expertise to be provided by MECS).

In one of the discussions, a couple of people said that electric cooking was very expensive. I argued that a financed electric cooking system could end up being cheaper than spending ($24*) a month on a sack of charcoal, but we agreed that it would always be too expensive for people gathering firewood for free.

In their introduction, E4A was described as a response to burgeoning interest in mini/micro grids. The theory of change appears to be that, in the same way that LED light bulbs enabled solar home systems to provide lighting service at affordable cost, the advent of efficient appliances will enable people to enjoy additional services at affordable cost. But does cooking with electricity fit into this theory of change?

We have previously taken the view that modern energy cooking devices will mainly be adopted by people who currently pay for their cooking fuel(s) i.e. where a substitutional expenditure exists. In the same way that $10 a month expenditure on kerosene for lighting could be used to pay monthly instalments on a SHS or mini grid. However, as independent grids tend to be installed in rural areas, where most people are likely to cook with firewood or locally produced charcoal at low cost (i.e. minimal substitutional expenditure), it might be difficult to justify cooking with electricity, no matter how efficient the device is.

However, the theory of change presented by E4A makes no direct mention of substitutional expenditure, it talks about feasibly delivering energy services (e.g. cooling, refrigeration, productive uses). So could we argue that providing a smoke free kitchen is a valued service? Or providing a domestic appliance that reduces the burden of washing on women (cleaning clothes that get soot on them, scrubbing soot off the bottom of pots) is a similarly valued impact on quality of life?

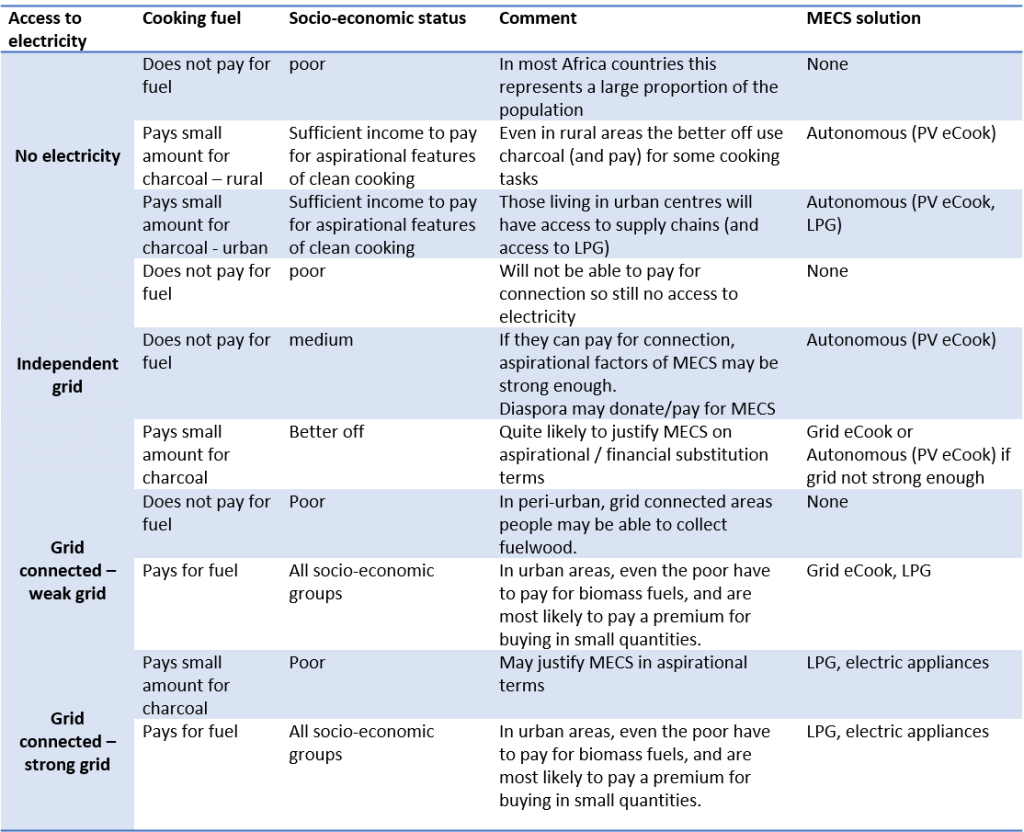

All of this illustrates the importance of considering the role of cooking with modern energy in different contexts, or market segments. Viable options also depend on compatibility with geographical and other factors e.g. LPG relies on a supply chain. Thinking continues to evolve, but here’s what we seem to have at the moment:

I asked to publish this because on Thursday, LCEDN 8th Conference is spending a whole day on Theory of Change in Strathclyde. It’ll be great to have this little element debated.

Other questions to raise are;

Do you get independent grids in trading centres where there is no grid?

Do you get grid connections in rural areas (where people can gather fuelwood)?

*I said $24 in the meeting because I had recently read that, but of course there are a whole range of expenditures.