- Date

- 25th May 2022

- Categories

By Dr. Richard Sieff (Loughborough University), Dr. Ashutosh Sharma, Saumya Vaish, and Dr. Chandrashekhar Singh (IRADe).

A recent MECS Electric Cooking Outreach (ECO) pilot study in Nepal has demonstrated how quickly people in both urban and rural communities can adopt electric cooking (eCooking) and transition to using the technology on a sustained basis. The five-month pilot reached 80 households in two women communities in Kavrepalanchok district: 40 from Sahara Nari Chetna Skill Cooperative, a women community in Banepa urban municipality, and 40 from Sabal Nari Chetna Agriculture Cooperative, a women community in Timal rural municipality. The study was conducted by the non-profit, research institute, Integrated Research & Action for Development (IRADe), with project partner, Women Awareness Center Nepal (WACN) and assessed whether electric pressure cookers (EPCs) were compatible with the local electricity supply and the socio-economic and cultural context of the communities.

Swift and sustained eCooking transitions lower fossil fuel use

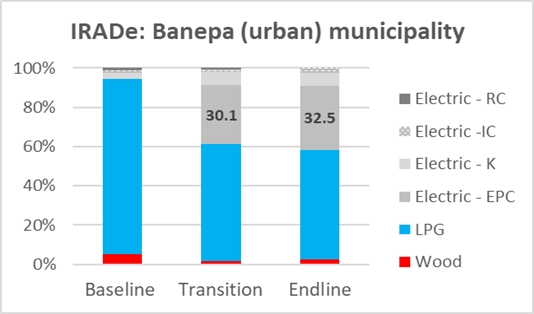

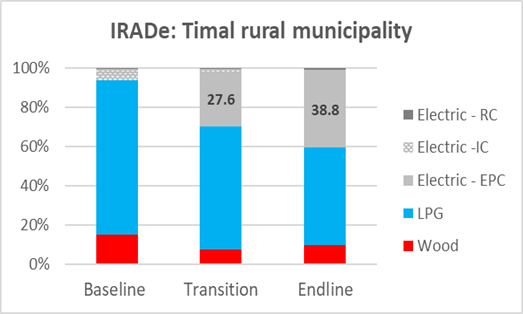

During the pilot, subsidised EPCs were distributed to the 80 women participating in the study, with usage monitored through cooking diaries, energy meters and surveys. Results from the cooking diaries showed the transition to eCooking was particularly swift (Figures 3-4). At the start of the pilot, LPG was the main fuel of choice, accounting for 89% of cooking events in Banepa and 79% in Timal, while electricity only accounted for 6% in each community (use deriving from kettles, rice cookers, and induction cookers). Once introduced, EPCs accounted for 30.1% and 27.6% of cooking events in Banepa and Timal respectively, resulting in LPG use falling to 59% (Banepa) and 62% (Timal). By the endline phase (month 5), use of EPCs had increased further still to 32.5% (Banepa) and 38.8% (Timal). The higher eCooking usage in Timal was partly driven by LPG being more expensive than in Banepa due to difficulties in transporting the fuel to the community’s rural location.

Women community networks facilitate successful adoption of eCooking

Households were overwhelmingly positive about the EPC. Although cooking took slightly longer, the women participating in the study liked that the EPCs did not need to be continuously monitored, enabling them to carry out business activities and other household tasks. Participants praised the cost effectiveness of the EPC and were very conscientious of the large savings they were making compared to LPG. Households also liked that they could cook most dishes on the EPC and reported food tasted just as good and sometimes better compared to their previous stoves, with chicken and meat dishes more tender. Overall, the menu changed little during the pilot, indicating the EPC fits local cooking practices.

“Food cooked on EPC tastes very good, as it evenly cooks the food, and I can do other work while the food cooks on EPC. I would prefer electric cooking as it is cheaper than LPG.” (Banepa resident)

Inter-community support was another notable feature of the pilot, with younger participants – who tended to adopt the technology more quickly – helping older community members to use the EPC. This community support facilitated the swift and sustained eCooking transition and also led to innovations in EPC use, particularly in Banepa where some households began using bowls as separators to enable simultaneous cooking of rice and pulses (Figure 5).

Product quality and after sales services drive uptake

The positive user experience saw many households express an interest in buying a second EPC to facilitate simultaneous eCooking. Many households other than the study participants have planned to place a joint order in time for the local festival to avail bulk/festival discounts. People were keen to buy the same model used in the pilot despite the device being one of the most expensive in the Nepali market. This was due to their positive experiences during the pilot and because the EPC was from a well-known international brand, which was consistently available in the Nepali market, with dedicated in-country repair and maintenance centres which increased confidence in the technology. At present, the repairing centres are mainly located in Kathmandu. The provision of local eCooking after sales services will reduce the apprehension of people about the EPC thereby promoting its uptake.

Electricity reliability issues limit households from using EPCs as much as they want

To expand eCooking uptake further, a greater focus on addressing the reliability of grid electricity is required. Voltage quality was an issue during the pilot and when power cuts occurred, 50% of participants reported the interruption forced them to switch to other cooking fuels. Furthermore, households mainly used their EPCs between 6-9am and 5-8pm, coinciding with peak electricity demand, which could cause issues for up scaling eCooking if grid reliability and demand side management are not improved.

Conclusions and next steps

The findings from the project further strengthen the evidence base for eCooking in Nepal by highlighting how women communities can support swift, significant, and sustained eCooking uptake. The project also shows how the quality of the product and the availability of after sales services are crucial for inspiring consumer confidence in eCooking and can lead to increased demand for eCook appliances. To realise the clear opportunities for a greater shift to eCooking in Nepal, increased efforts are required to develop a more reliable electricity system. Consumer awareness campaigns and improved quality benchmarking are needed to support eCooking at scale as many households are unaware of the benefits of eCooking or which eCook devices to purchase. Research is also required into how innovative financing solutions might address the potential upfront cost barriers of purchasing an appliance and facilitate more inclusive eCooking transitions.

For more information on the study, the IRADe ECO final report is available on the MECS website.

……………………………………………..

Featured image, top: Community lunch prepared in EPCs. Image credit: IRADe, 2021.