- Date

- 8th November 2024

- Categories

- Carbon Finance, Just Transition, Social Inclusion

By Dr Samir Thapa, Loughborough University

In this blog I attempt to highlight the distributional tenets of just cooking transitions reflected in the preliminary think-piece on Just Cooking Transitions (Briefing Note) through an analysis of the requirements of carbon project fees and contributions in country level regulations.

The 2015 Paris Agreement (PA) seeks to achieve a consistent pathway that limits global average temperature rise to between 2 to 1.5°C through emissions reduction and removal activities including those designed as part of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), Long-Term Low Emission Strategies (LT-LEDS) and National Adaptation Plans. Its Article 6 (A6) constitutes market based flexible mechanisms for A6.2 International Transfer of Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs) and the structured issuances and use of A6.4 Emission Reduction (ER) credits including the traditional non-market A6.8 approach. The PA emphasises A6 implementation considering differentiated responsibilities, vulnerabilities, and impacts across Parties1 within the broader frameworks of climate justice, governance, transparency, and equity, for just transition. This calls for going above and beyond on imperatives and obligations of in relation to human and labour rights, secured jobs and poverty eradication, health and education, gender equality and empowerment, also for the indigenous and local communities, migrants, children, and people with disabilities.

Going forward, A6 implementation will increasingly require countries, crediting programs, and project proponents to explicitly consider Sustainable Development (SD) benefits beyond SDG13 and safeguards against impacts. This would mean putting in place procedures, guidance, and tools to abide by national/local regulations, conduct appropriate local stakeholders’ consultations, and assess/manage associated risks, and adequately ensure and allocate SD benefits. In this, A6.2 guidance mandates reporting SD in its Initial Reports and in subsequent regular Biennial Transparency Reports, which will draw both from the recently released A6.4 SD Tool and/or the Integrity Council for Voluntary Carbon Market SD and Safeguard2 requirements.

The A6.4 SD Tool has incorporated fair distribution of development opportunities and benefits linking it to national laws and international instruments, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights within its social safeguard elements, which was lacking in the earlier versions of the tools and approaches. Carbon financing regulations of some early mover countries also explicitly require SD benefits and safeguards assessment as per national laws and priorities. However, these requirements are mostly conventional3 and performed as per the country’s existing legislation, strategies, and priorities. Most commonly, projects are required to indicate expected employment creation, gender contributions, conduct local stakeholder consultation, and assure participation in project designs.

Interestingly, implementation and support for policy approaches and positive incentives, primarily including results-based payments for activities Reducing Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) is clearly mentioned under PA Article 5.2. Further analysis shows this emphasis on support and incentives for forestry and land-based activities are reflected in Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM) and country level regulations as well. The Integrity Council for Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) requires benefit sharing to be considered as part of SD benefits and safeguards criteria, but only if independent crediting mechanisms requires benefit sharing arrangements. This arrangement is implied to be required only for land-based activities and for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities.

In this, activity proponents shall develop a benefit sharing plan, which are appropriate to the context and consistent with applicable national rules and regulations. Then again, in the national regulations, it is common to find specific requirements and recommendations on sharing carbon revenues only for forestry-based projects, more so for REDD activities (e.g. Nepal, Ghana, Tanzania). Some of these contains clear and detailed distribution schedules for various stakeholders (e.g. Tanzania, Kenya). While this is understood to be a legacy payment for eco-system services practice adopted subsequently in related legislations often prepared by forestry and/or environment ministries, it is also a manifestation of the emphasis on the policy and positive incentives specified as part of the higher-level PA Article 5.2, which specifically emphasises results-based payments for jurisdictional projects under REDD.

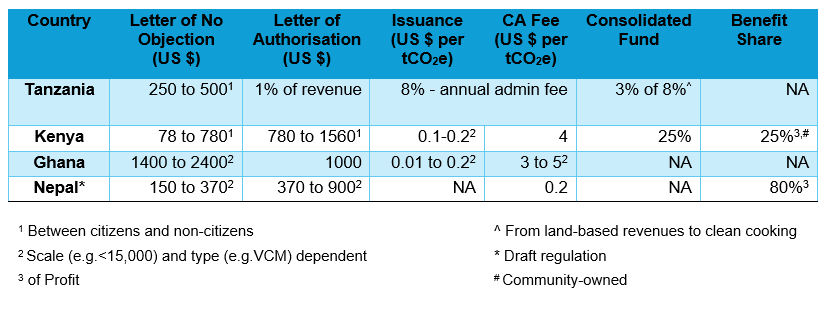

Paragraph 33 of the Annex to the Decision of CMA3 on Rules, Modalities and Procedures for A6.4 states that A6.4 methodologies shall contribute to equitable sharing of mitigation benefits between participating Parties. Through a rigorous A6.4 SB process of developing the standards, this condition has been reflected in the draft standard for mechanism methodologies, wherein participating parties can use different approaches to demonstrate equitable benefits sharing. While this condition allows flexibility to develop models for benefit sharing within the Parties provisions, early indications show that the host Party regulations are heterogeneous (Table 1 4) and not sufficiently clear for non-land-based and/or REDD activities, especially for revenue sharing. For example, in the case of Kenya and Nepal5, 25% and 80% of the profit is required to be shared with the consumers respectively. However, project developers are not sure what factors would entail project costs e.g. capacity building and awareness. Moreover, for Kenya, it is unclear how such projects are required to share this as annual community contributions if developed within the framework of public and community projects since clean cooking projects are often developed as private projects on private land.

Country regulations may also require additional revenue contribution to a consolidated fund. Kenya in its recent regulation requires non-land based projects e.g. clean cooking projects to contribute at least 25% of the previous year aggregate earnings to its Climate Change Fund. Tanzania’s regulation is different in that it requires 3% of its 8% gross revenue collected from the land-based activities to be deposited in its National Environmental Trust Fund, to promote clean cooking. Rwanda and Zambia have also prepared comprehensive framework/s and guidelines6 respectively on their carbon market readiness but without spelling out conditions for sharing benefits and revenues.

The combination of enhanced leadership on revenue sharing by host Parties and guidance by the A6 process as well as the willingness of project developers indicates a shifting sectoral perspective. This could deliver innovative business models different from existing ones which are often built to continue providing general upfront subsidies against rights to credits. However, literature shows that such general ‘recycling’ of carbon revenues to continue upfront subsidy models, can result in substantial welfare losses. This is, due to, among others, unequal access to such subsidies, their increased delivery costs and missed psycho-social opportunities with rewarding revenues, where studies reveal that revenues are better integrated into mainstream financing e.g. incentivising interest subsidies on purchase loans. Recent pilots on revenue sharing by ATEC based on IoT enabled usage data monitoring and revenue transfers via mobile phone proportional to electricity use, offers more effective ways of tying up revenue sharing e.g. to nudging. These examples have shown that sharing revenues can result in higher credit prices, especially with the innovative dMRV frameworks which are also expected to enhance market credibility.

Sovereign country level leadership and innovations in enacting coherent carbon market regulations with clear benefits and revenue sharing models will be crucial in delivering the distributional tenets of just cooking transition practices. This is expected to be complemented by a mix of premium prices, and how countries and communities (e.g. West and East African Carbon Market Alliance) align and pitch their comparative advantages. In this, it will be crucial to consider revenue sharing models that can ensure sustained operation e.g. through digital and/or robust monitoring and those that can leverage mainstream finance to achieve the scale required. Therefore, guidance on appropriate carbon revenue sharing mechanisms should be part of the assistance and capacity building support during the preparation of country level strategies, regulations, and frameworks.

***************************************************************************************************************

1 The UNFCCC entered into force on 21 March 1994. The 198 countries that have ratified the Convention are called Parties to the Convention.

2 Integrity Council for Voluntary Carbon Market (IVCM) developed its Core Carbon Principles (CCPs) and their Assessment Framework, on existing CORSIA eligibility framework, to assess mechanisms and their credits. The safeguards include against human and labour rights, resource efficiency and pollution, land acquisition and involuntary resettlement, biodiversity conservation and sustainable management of living natural resources, IPs and LCs, and cultural heritage, and gender equality. REDD+ activities must be consistent with all relevant Cancun Safeguards as set out in paragraph 71 of decision 1/ CP.16 of the UNFCCC.

3 For example, Kenya, Ghana, and Zambia requires projects to conduct environmental and social impacts assessment as per the respective legislations. Further, activities are required to prioritise SDGs as per country’s SDG strategies and guidance, if available, otherwise use international SD frameworks, tools, and methodologies, including for monitoring safeguard provisions and SD benefits (e.g. GS and A6.4 SD Tools).

4 A6.4 plans to charge US $ 1,500 to 10,000 for registration depending on the estimated credits issued and US $ 0.15 per tCO2e during issuance. GS charges an annual account fee, a registration fee of $0.10 per credit of nominal credits estimated over the crediting period, and another $0.10 per credit for issuances thereafter.

5 Nepal is drafting its Environment Protection Regulation (First Amendment), 2024.

6 Zambia is preparing three more guidelines, and Guideline on Share of Proceeds may include revenue sharing measures, but it could be lacking given that the parent legislations, especially its Climate Change Act that could incorporate high level provisions for regulating the carbon markets including benefits and revenue sharing are yet to be approved.

***************************************************************************************************************

Featured Image: Designed by Freepik, www.freepik.com.