- Date

- 4th June 2019

- Categories

By Dr Nigel Scott, Gamos

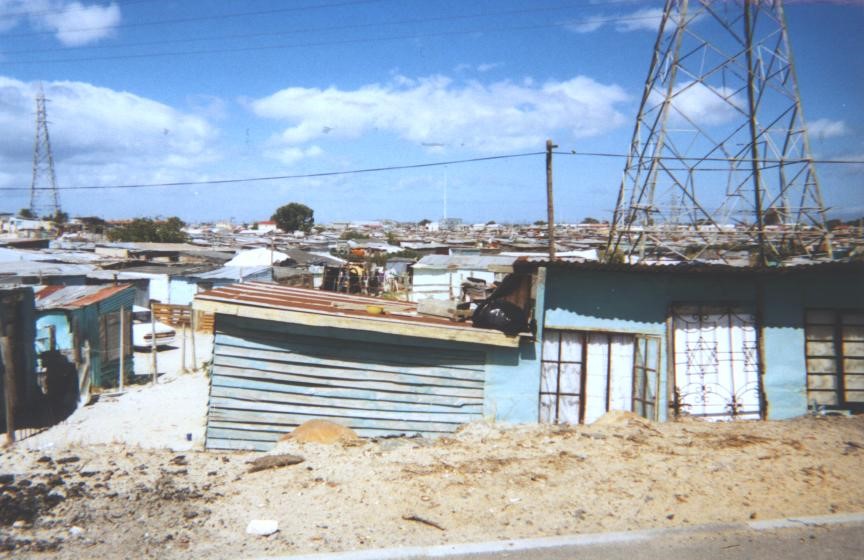

At the recent LCEDN conference, Ben Campbell described the nature of displaced communities being studied under the ‘Energy on the Move’ programme (not to be confused with the Moving Energy Initiative). Raihana Ferdous gave a really interesting description of informal settlements in Bangladesh, where displaced people tend to relocate into urban communities. In terms of energy access, one of the key points is that authorities are reluctant to provide services to these communities as doing so would tend to legitimise them – something they are opposed to for a whole variety of reasons. As a result, most residents get electricity through a number of informal/illegal methods. One thing all of these methods have in common is that they are sub-standard and hazardous – the grid supply is weak.

Households on weak grids are a set of consumers that the MECS programme needs to consider. Households in informal, urban settlements like those described by Ben are a priority group because although they may have electricity, the supply is too weak to use for cooking. Instead, they have to buy biomass fuels, typically charcoal, and being poor and having minimal storage space in their kitchens, they are forced to buy in small quantities, meaning they pay the highest prices for cooking fuels.

But what do we mean by weak grids? Technical definitions focus on voltage drops that occur when loads are added to the local grid; for example:

“a grid where it is necessary to take voltage level and fluctuations into account because there is a probability that the values might exceed the requirements in the standards when load and production cases are considered” Bindner, H. (1999). Power control for wind turbines in weak grids: Concepts development. Denmark. Forskningscenter Risoe. Risoe-R, No. 1118(EN)[1]

Even more technical notes talk about the electrical reactance of the grid (resistance to the flow of electricity), and define a weak grid as having an Xgrid/Rgrid ratio < 5 (the ratio of the reactance, X, to the resistance, R, of the grid).[2]

In many countries, low voltage can indeed prevent people from using electricity for cooking. The power rating of cooking appliances is proportional to the square of the voltage, so halving the voltage results in just a quarter of the power. In Myanmar, for example, extreme voltage fluctuations were observed, especially in rural areas, where a voltage of 20V was observed on a grid designed for 230V!

At a recent gathering convened by EST under the LEIA programme, Anne Wacera from Strathmore University in Nairobi, an engineer who works on electrical standards, took quite a different approach. She suggested that categorising a grid as weak or not depends on what you want to use the electricity for. For example, if you want to pump water to a holding tank, then as long as the electricity is available for few hours a day the supply is strong enough. If you want to cook, but the electricity goes off for 20 minutes when you are frying vegetables, then the supply is not adequate. And if you are a brain surgeon, losing power for a second could be catastrophic.

If the voltage drops, then it may still be possible to use standard electrical appliances for cooking if used in conjunction with a voltage regulator. Of course it depends on how low the voltage drops, as regulators can typically cope with voltage fluctuations of around ± 10-20%. Remember that a 700W appliance will only operate at around 450W if the voltage drops by 50%, so it may still not be possible to cook as normal. If the voltage drops even lower, or if the power goes off altogether, then cooking can be done with some kind of appliance that is integrated with a battery.

On the one hand, the MECS programme, in collaboration with others such as LEIA and Global Leap, will be supporting private companies to develop these kinds of appliances. At the same time, it will be interesting to try to get a better understanding of potential markets in developing countries, to make some kind of estimates as to what proportion of electricity consumers are connected to weak grids – where that may be defined as a supply that is simply not good enough for them to use for cooking with electricity.

[1] http://orbit.dtu.dk/files/7729819/ris_r_1118.pdf

[2] https://www.ieee-pes.org/presentations/gm2015/PESGM2015P-000975.pdf