- Date

- 31st July 2024

- Categories

- Clean Energy, Solar eCooking

By George Foden, Loughborough University

We don’t often think about the wider impact of our everyday activities on our health and wellbeing, and even less about its potential impact on global climate change. Seemingly innocuous behaviours, when practiced by a large number of people, can have a disproportionate influence on a society’s greenhouse gas emissions. For example, the Clean Cooking Alliance notes that about 25% of global black carbon emissions come from household cooking, heating, and lighting. In some African countries, this can be as high as 80% of black carbon emissions. Health research undertaken in Malawi demonstrates the wider impacts cooking with dirty fuels can have, not just in terms of climate change, but also on the health and wellbeing of people using these fuels.

Malawi also has another significant issue to deal with when it comes to the use of dirty fuels in households across the country. A favoured building material by many engaged in informal construction of their own homes, is burnt bricks. Bricks are burnt using wood or charcoal in ways that are often very inefficient, with estimates suggesting that up to 850,000 tonnes of wood are burnt by brickmakers annually, releasing 1.5 million tonnes of carbon emissions.

The MECS programme is focused on shifting technology and behaviours to improve health and wellbeing outcomes, and does so in Malawi through programmes like Solar4Africa. Similarly, in my recent field research trip in the southern region of Malawi, I spoke with several NGO staff who were attempting to tackle the emissions of burnt bricks by improving efficiency and finding cleaner fuels, in collaboration with community brickmakers. Through these sorts of programmes, organisations are hoping to incentivise cleaning and construction behaviours that reduce environmental impact, rather than punishing use of dirty fuels. But at the same time, the Malawian government is moving towards the outlawing of the use of dirty fuels, utilising the ‘stick’ to punish ‘bad behaviour’ at a great cost to some of its poorest citizens.

The ‘Sticks’

The drive to outlaw the use of dirty fuels in cooking and construction in Malawi is a strong one. In 2017, the government of Malawi announced its National Charcoal Strategy, which took a holistic approach to drive the reduction in use of charcoal across the country. It had multiple pillars aimed at advocating for cleaner cooking and supporting livelihoods utilising new fuel options, and just a few years after its launch it was Pillar 4 that was the most clearly visible in practice: strengthening law enforcement to crack down on people who were using unlicensed charcoal.

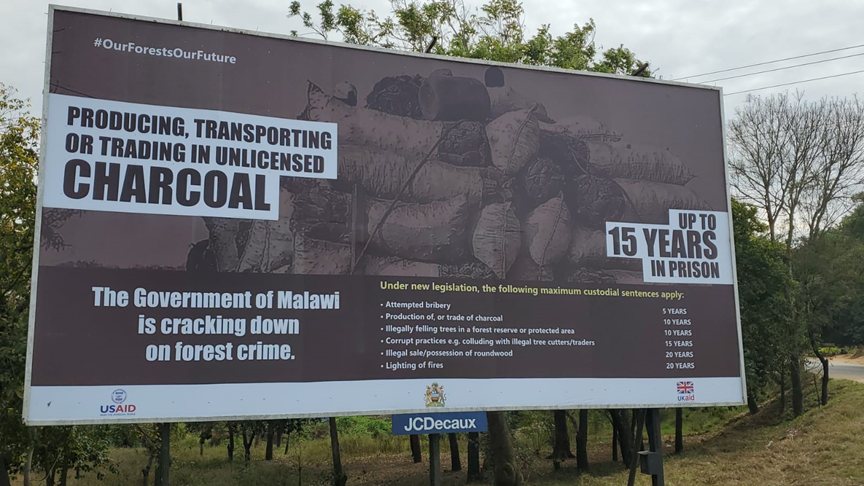

In a visit to Malawi in July 2022, Robert van Buskirk, co-founder of Solar 4 Africa, shared this photo of a warning sign seen near Machinga with some of the MECS team, with the following note:

Here is one clean cooking solution: throwing people in jail… This is just my opinion: But I personally think that it is a much better use of aid to subsidize solar panels than it is to use the aid to subsidize throwing poor Malawians in jail.

In December 2022, over 5 years after the National Charcoal Strategy came into effect, the Nation reported that 80% of Malawians were still using illegal charcoal, largely because of the inaccessibility of more efficient fuels due to their cost. An analysis of the increased enforcement from the USAID and UKAID-funded Modern Cooking for Healthy Forests found that, despite increasing convictions and penalties, charcoal use had not been curtailed. They advocated for the development of sentencing guidelines to standardise prosecution procedures in Malawi, but Robert sees things as simpler than that:

My advice to the powers-that-be is that they pull this threatening and hostile enforcement campaign (which targets hundreds of thousands or millions of Malawians who participate in unregulated charcoal business) and replace it with an enforcement message that is more friendly and educational.

In a meeting for the Malawi Shelter Cluster in Salima in October of last year, I found myself caught up in a discussion between national and international NGOs and local government actors exploring construction methods for post-disaster housing across the country. They were attempting to standardise housing designs to make the reconstruction process simpler, and part of the debate was around government guidance for NGOs to avoid the use of burnt bricks in their housing designs. In 2018, the National Construction Industry (Use of Sustainable Construction Materials) Regulations banned the use of burnt bricks in commercial and public buildings, and now there was pressure on the NGOs to avoid the use of burnt bricks in their post-disaster housing designs as well, something that fed into the updated guidance on the Safer Construction Guidelines laid out by the Malawi Shelter Cluster.

But outlawing the use of burnt bricks on the part of large scale construction has done little to curtail the practice in communities across the country. In the projects I visited in Chikwawa, Nsanje, Zomba, and Blantyre, community members were either using burnt bricks in their own self-reconstruction activities or were reluctantly adopting the stabilised-soil bricks (SSB) that the NGOs were advocating. Despite research showing that SSBs can be suitable alternatives to burnt bricks in Malawi, the people that I spoke to were uncertain about adopting this new material in their own construction practices. As one brickmaker, who had been trained how to make SSB bricks and was being paid as part of the NGO programme, explained to me during my research:

People will not buy these [SSB] bricks at 50 kwacha… People also prefer burnt bricks so convincing people to buy these ones will be difficult… I personally would prefer burnt bricks, but we don’t have a choice.

There was clear concern amongst shelter practitioners that the use of burnt bricks would return as soon as their programmes came to an end, with multiple NGO staff expressing their frustration with the approach.

What about using a carrot?

The outlawing of undesirable materials does not appear to be working in Malawi in terms of reducing the use of charcoal or other dirty fuels. If we accept that this approach does not work, is there another way to address these issues?

Solar4Africa have been working in Malawi since 2015, exploring the most effective ways to incentivise the use of clean energy in cooking amongst ordinary households. In that time, they have had some great successes, which were inspired by their learnings from past experiences. The project has found success in incentivising the use of solar panels for clean cooking with electric pressure cookers across the country, by empowering women’s groups to run their own businesses selling the cookers, but this was not the first approached trialled, as Robert explained. At first, they tried to use the stick, confiscating solar panels when payment wasn’t received on-time etc., but after 9 years of seeing the stick did not work, they decided to just use the carrot.

Cost efficiency is key. If you try to use the stick to punish people for bad behaviour, you bear the cost of wielding the stick. With a carrot, you can show them how it works, and your audience will bear the cost of coming to the carrot. It took us a long time to understand this, but at the end of the day, sticks are more expensive than carrots.

Solar4Africa will be seeking to create a network of 200 – 300 solar shops by the end of 2025. If the carrot is beginning to work for Robert and solar based cooking, is there an equivalent in the construction business? Ultimately, something like the ATEC cook to earn is perhaps the ultimate carrot, and Solar4Africa are working towards strategic leveraging of finance for co-benefits – a bigger carrot.

“Sticks are more expensive than carrots” – It’s a message that should be taken into consideration as we continue to move towards cleaner energy for cooking, construction, and household use.