- Date

- 22nd July 2024

- Categories

- eCooking

By Jacob Fodio Todd & Richard Sieff (Gamos Ltd.).

Building on a recent MECS working paper, this blog explores two contexts for modern energy cooking – institutions, commonly organisations with a more public serving purpose such as hospitals and schools (which are a key focus of the World Food Programme), and commercial organisations, that are business or profit-led ventures, such as restaurants and fast-food restaurants. Sometimes lumped together, this blog explores how the modern cooking needs of commercial and institutional settings can actually be quite different from each other, and from that of households.

Household level knowledge of eCooking in Africa and Asia has advanced rapidly in recent years and many of the core lessons are applicable to the commercial and institutional arena. A range of research methods such as cooking diaries, discrete choice modelling, controlled cooking tests, household surveys, focus group discussions and kitchen performance tests – employed by MECS, partners and colleagues – have delivered data on how people cook, their energy consumption and opportunities for energy and cost savings. While there are similarities and lesson learning that apply to all contexts, there are nevertheless variations between the household, institutional and commercial contexts, ranging from the technical to the culinary to gender dynamics and supply chain perspectives.

One fundamental area of divergence between residential, on the one hand, and commercial and institutional, on the other, is scale: the largest households cater from the individual to the low tens of people, while the other domains cater from tens to many thousands. In practical terms, it means that institutional and commercial settings often have large areas of overlap from a technical perspective and many larger eCooking devices will serve both contexts equally well. Importantly, at large scales, incremental changes to energy efficiency can quickly produce big savings.

Other motivations and concerns also impact the suitability and practicality of adoption of eCooking devices in institutional and commercial contexts. Yet, compared to the household level, there is far less baseline research on the energy demands or knowledge of these spaces; a clear gap in the academic, grey, and industrial literature. As work in this area continues to build and an under-researched area of study develops, we outline some views and hypotheses from initial research and recent discussions, including a focus on the differences between the modern cooking needs of commercial and institutional settings.

Institutional eCooking opportunities

A key point of differentiation between institutional and commercial settings is that an institution’s primary concern is not usually food, therefore giving it a longer-term view of returns on any investment in kitchen equipment. A school is an educational institution, a hospital is a medical setting, and a prison is a criminal justice facility. None of their primary functions are to serve food, yet to varying degrees, many do. Often, they are not profit-led, and are state run or centrally funded or supported (albeit in instances, services will be outsourced to the private sector). Although this may mean that they have budgetary constraints and are under pressure to act parsimoniously, given that their longevity is unlikely to be dependent on the success of their catering operation, institutions should be able to take a longer-term view. The cost of investing in equipment, in theory, will have time to amortise, an important factor where higher capital outlay is required, as may be the case with large energy-efficient technologies, such as novel large-scale eCooking appliances. A long-term perspective provides more time for the day-to-day cost, and time saving benefits to accrue.

Early eCooking research in schools is promising and daily meals provide a strong incentive for attendance and potentially improve educational outcomes. Early evidence from research in schools in Lesotho and Kenya1 suggests that eCooking can lead to time and cost savings, reduced water use, a safer kitchen environment and less food waste. Indeed, schools are the site of some of the most recent developments in institutional modern energy cooking, led by organisations such as the World Food Programme (WFP) through their school meals programmes. Daily meals provide a strong incentive for attendance, counter high rates of student absenteeism and reportedly improve academic performance.

Single dish batch cooking has traditionally been popular in institutional kitchens. Culinary analysis from recent MECS research is so far supporting a hypothesis that institutions like schools will favour offerings that are uncomplicated, consistent (i.e. in terms of menus), nutritious (under budgetary and food availability constraints) and cooked simply to preserve those values. This is demonstrated well by ongoing work by Alianza Shire in a refugee camp school in Ethiopia and a recent MECS researcher visit to a Day-care Centre in Malawi that caters to 140 infants and young children every weekday. In both cases, the institutions provide the attending children one daily meal of porridge boiled in one large vat (Image 2).

This kind of single ingredient or single dish batch has traditionally been a strength of eCooking appliances which are able to regulate accurately and produce consistent results with thermostats, timers, and other forms of automation2. They are particularly effective in processes that need to be standardised and specialised, as is common in both commercial and institutional settings, minimising risk and saving time.

The clientele of institutional kitchens are less demanding. Food in institutional settings is, arguably, less reliant on clientele feedback loops (e.g. on taste), and more uniform (the same dishes cooked in the same way on a regular basis). In some cases, food and menus are approved at government level, such as in Sri Lanka, with the Ministry of Education. Consistency is a useful trait in making long-term food and energy decisions.

Commercial eCooking opportunities

For the purposes of this discussion, commercial organisations are defined primarily as profit making organisations or businesses, such as restaurants, hotels, street food vendors or cafes. As a key motivation is financial, their success is dependent on both the attractiveness of the food offering (flavour, cost or both) and the ability to serve food at a profit3.

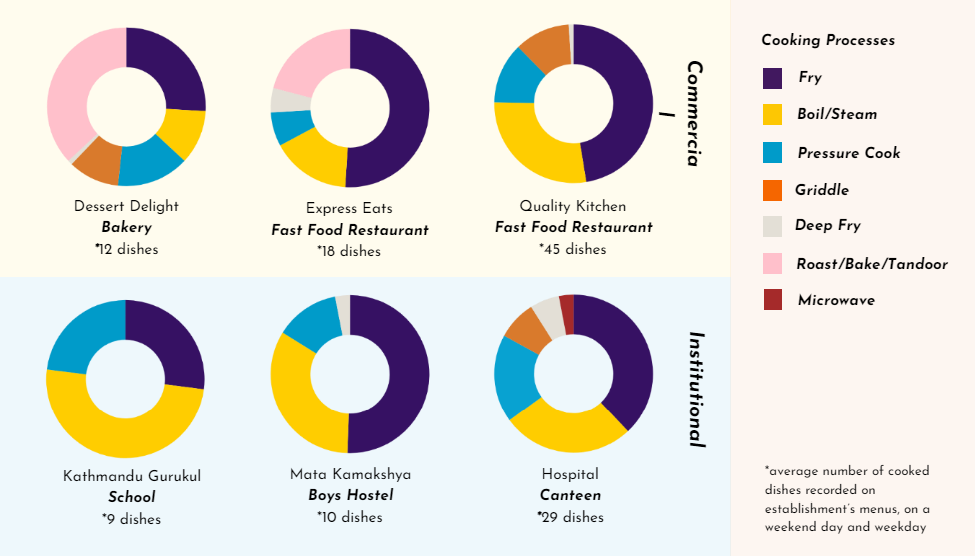

More demanding clientele leads to greater variety of higher quality dishes. To address this taste driven profit-making concern, MECS research in Nepal shows commercial organisations tended to have broader menus and deploy a wider range of cooking process using a greater range of appliances and utensils (Figure 1). Specialist equipment, such as deep-fat fryers, or reserving effective cookware for certain techniques (e.g. woks for stir-frying), is also common to many operations.

Other trends, such as urbanisation, make the commercial eCooking sector an interesting growth area. Globally, but sub-Saharan Africa in particular is rapidly urbanising and eating out is a growing trend in urban areas, as discussed in this Modern Eating landscape paper, one of the MECS outputs to tackle commercial eCooking. A shift of energy use for cooking from urban households to commercial establishments is therefore likely to continue4, both moving outside the household and changing inside, as pre-processed foods (e.g. canned food) and bought-in foods (e.g. chapatis or bread) become more commonplace. Electric cooking in industrial settings is another area that the MECS programme has started, and will continue to, explore.

Opportunities for institutional and commercial eCooking

Insulation and pre-bought foods mitigate long service hours. Insulation often plays a critical role in both commercial and institutional applications as there are often longer and more consistent preparation and service hours than households. This characteristic can often be seen among the more informal sector and street food vendors; for instance, in Kenya, a one-person smokies vendor might heat their food and then use an insulated vessel to keep food warm throughout the afternoon or evening. Insulation and reheating equipment (e.g. hot holding and microwaves), can be of great benefit in commercial and institutional settings. Vendors often supplement their core cooking with pre-bought and processed goods (burger buns, sauces, dough, chips, etc) to improve time efficiency, especially in commercial contexts. A smokie itself for instance is purchased pre-cooked, and served reheated on the streets.

Taking advantage of time of use tariffs and avoiding peak demand. There are opportunities for institutional and commercial organisations to connect to broader energy or clean cooking policies, as the co-benefits are manifest. As we report in a recent working paper which synthesises findings from research in Nepal by Practical Action Consulting and Women Network for Energy and Environment (WoNEE), some organisations revealed that they could provide flexible demand by shifting batch cooking and food preparation to when tariffs are lowest, using time of day meters. In countries with a high renewable energy mix, such as hydropower or solar, this could prove particularly advantageous as even if serving during the evening, cooking can be, and often is, at larger scales conducted over many hours, potentially in those times when there might be a surplus of electricity generation, and lower tariffs. This flexibility could help to avoid adding to peak electricity demand periods and absorb surplus capacity, thereby mitigating the pressure on electricity infrastructure and potentially supporting the profitability of the utility.

Conclusion

There are many recommendations for the household level that are commonly employed with commercial and institutional level cooking. A good example of this is batch or bulk cooking to increase energy and time efficiency. A larger domestic kitchen for example might cook 1 kilo of rice for use over a day while a commercial kitchen might prepare 10kg, for that day, subsequent days, or for multiple different menu uses (e.g. served hot as plain steamed rice, cooled to later make fried rice, or used to make a rice drink). A base tomato pepper sauce might be cooked and used for jollof rice, red-red (beans), meat stew or simply as simply sauce. Other mechanisms for energy and cost saving have also been emphasised in household studies, among them insulation and reheating equipment (e.g. EPCs, rice cookers).

In sum, transitioning to eCooking might mean increased efficiencies from commercial and institutional organisations. It could lead to more people being served, doing more with less funding in institutional settings, and higher profits in commercial settings. However, uptake of eCooking in the Global South often suffers from entrenched views around cooking with electricity, a relatively new cooking technology. Although globally electricity access is expanding, access is asymmetrical and still not universal. In all settings, kitchens and cooking environments are often the most energy-intensive parts of buildings or households and pre-existing wiring, meters and other electricity infrastructure may require upgrading to support eCooking, an issue exacerbated when three-phase power is required for more power-hungry appliances.

Practically, supply chains, are typically still developing for domestic eCooking in much of the Global South, and likely less advanced still in institutional and commercial spaces. Additional challenges are present with large-scale eCooking appliances in terms of the size, greater variability in cooking pot sizes (10s to 1000s), and smaller demand volumes which can present transport and logistics problems. Discussion and research has also focussed on how these different settings vary by broader context, such as when situated within camps for displaced people.

To support the potential for commercial and institutional eCooking transitions highlighted in this blog, interventions are required to address such challenges. Integrated electrification and clean cooking planning could help mitigate issues concerning organisational electricity infrastructure deficits while greater awareness raising of the benefits and availability of commercial and institutional eCooking appliances could help develop supply chains. All these considerations are ones that colleagues are working on, and we hope to generate more data and insights in the coming years, as momentum builds.

……………………………..

Footnotes:

1 Link to studies. (Pastorino et al., 2023).

2 Common examples of single ingredient eCooking include boiling water in kettles, and browning bread in toasters. Rice cookers and more recently, EPC, are leading examples of eCooking appliances adept at single dish batch cooking.

3 Food manufacturers and processors also have clear opportunities to electrify their cooking processes and many already do as part of highly customised production lines. Despite being commercial or industrial (and sometimes institutional) entities, this piece focuses on distinct opportunities and challenges for organisations which are both the site of food production and service.

4 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00953.x

Image 1 (featured, top). Food being cooked in an all-electric commercial kitchen (image credit: Jacob Fodio Todd).