- Date

- 25th March 2024

- Categories

- Electric Cooking

By Dr. Rudrodip Majumdar, Assistant Professor, Energy, Environment, and Climate Change Programme, National Institute of Advanced Studies. Correspondence: rudrodip@nias.res.in

Presentation made during Panel Discussion at the International Energy Festival of Kerala (IEFK) 2024,

Energy Management Centre (EMC)-Kerala, India.

- Background: Residential Cooking Landscape in India is Complex

- Residential cooking in India exhibits vast regional diversity in terms of culinary habits (choice of food items, texture of food items, and ways of cooking), which in turn dictates to some extent the types of vessels used, and cooking fuel used.

- As per the Latest Census Report, out of 121 crore Indians, 83.3 crore (~ 68.8%) lived in rural areas, while 37.7 crore (~ 31.2%) stayed in urban areas in 2011.

- In terms of daily life cooking practices, the differences between the urban and rural areas are also quite prominent.

- At a further micro-level, differences are present within the urban settings (cities and towns) among the low-to-medium-income, and medium-to-high-income households.

- The wide range of food habits and culinary traits existing in India stems from the complex interplay amongst ethnic diversity, climatic attributes, soil types, religious practices, and cultural traditions (attributable to the historical landscape of the country).

- Many staple food items have come to India through trade relations.

2. A Peek into Elaborate Cooking Styles Prevalent in India

- Dum (steam) [‘maturing of a prepared dish’] is the forerunner of modern-day slow cooking. During the predominance of handi cooking, the utensil was sealed with atta dough (whole-wheat flour), to make the moisture stay within, and put on smouldering coal. Some of the coal was placed on the lid, to ensure an even flow of heat from top and below. Nowadays, the oven is used to perform the function of providing even heat.

- Bhunao (light stewing, sautéing, and stir-frying) is the process of cooking over medium to high heat, adding small quantities of liquid (water or yoghurt) in phases to prevent the ingredients from sticking, which also makes it necessary to stir constantly. The process is complete only when the fat leaves the masala (or sides).

- Talna (frying) is done in a Kadhai and a Deep fat fryer. A Kadhai requires a lesser quantity of ghee or oil, which makes it possible for the oil to be changed regularly. The shape of the Kadhai allows larger quantities of food to be fried and results in even frying. Food fried in clean fat looks good in colour, appearance, and flavour. It would also be free from the odour of reheated and burnt oil.

- Tarhka or Chhonkna (tempering) uses the extraordinary ability of hot oil to extract and retain the essence, aroma, and flavour of spices and herbs. The whole ‘garam masala’ is tempered before the rice is fried when making a pulao, or, cumin and hing are tempered and then added to the lentil when making dal.

- Dhuanaar (smoking) is a simple, but effective process for making dry meat delicacies. It requires charcoal, ghee, and a dry spice (usually cloves), and is usually done at the end of cooking.

- Bhunnana (roasting) is usually done in a charcoal-fired tandoor. The juices of the meat drip on the charcoal which sizzles and sends up billows of smoke, giving the tandoor a smoking chamber effect to kebabs, breads, vegetables, and paneer (Indian cottage cheese) a special aroma.

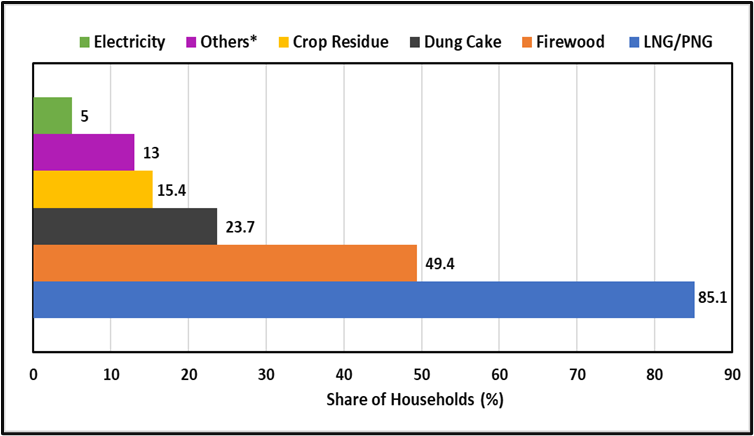

3. Breakdown of household cooking fuel in India in 2020 by type

This is based on face-to-face interviews conducted between November 2019 to March 2020 over 14,850 households. (Statista – September 2021). (Statista).

- The choice of food items, vessels, and cooking fuels can be analyzed and explained through the lens of the 4As (Availability, Accessibility, Affordability, and Acceptability).

- Such a conceptual framework would help us deal with ‘unknown unknowns’ in a better way through a constraint-based approach.

4. Issues with Different Cooking Fuels Options Prevalent in India

- In India, more than 75% of the rural and about 25% of the urban population use solid fuels (firewood, dung cakes, crop residue, coal/coke/lignite) as their primary source of energy for cooking.

- A District Level Household Survey (DLHS)-based study published in 2019 indicated that “individuals living in households where crop residue and coal/lignite are used for cooking suffer from asthma/chronic respiratory failure in the higher proportion as compared to others” [1]. (Faizan et al., 2019)

- The Global Burden of Disease Report mentions Indoor Air Pollution (IAP) as the leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in Southeast Asia.

- According to WHO, IAP from cookstoves results in 4.3 million deaths worldwide every year, accounting for 7.7% of the global mortality.

- The key health conditions attributable to IAP are pneumonia, stroke, ischemic heart disease (IHD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), lung cancer, and poor obstetric outcomes.

- Existing literature suggests that the regional statistics on access to clean fuels for cooking can be used as a surrogate indicator of disease risk.

- Despite intensified official interest since 2010 (formation of ministerial-level departments and programs that aim to make biomass combustion in Improved Cookstoves (ICs) as safe and satisfactory as compressed natural gas, new designs, and new distribution channels) very low public demand discouraged the private manufacture and marketing of ICs.

- Possibly the rural women targeted by development experts had different priorities and they did not share the same vision of a better life as those promoting the ICs. Social, cultural, and gender-political reluctances play a major role in community-level lifestyle choices [2]. (Meena Khandelwal et al., 2017)

- Recent studies have highlighted some Improved cookstove variants such as rocket and gasifier cookstoves to be more harmful to human health than conventional cookstoves due to the excessive presence of ultrafine air pollution particles [3]. (The Hindu, May 2023)

- LPG prices are linked with international crude prices and are sensitive to fluctuations in Rupee-USD parity.

- The average price of a non-subsidized 14.2 kg LPG cylinder (averaged over Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, and Kolkata) increased from ₹ 654.6 on 02 December 2020 to ₹ 1013.3 on 19 May 2022.

- The PMUY subsidy provided (₹ 200) covers only about 20% of the current non-subsidized cylinder price (~₹ 1050). Due to the sharp price rise, the number of nonsubsidized beneficiaries has drastically come down.

- Other factors that discouraged decent refill rates comprise inadequate area coverage of the LPG cylinder distribution networks and difficulty in subsidy disbursement for the population without proper bank accounts.

5. Insights from Initiatives in India Toward Energy Transition in Residential Cooking

- As part of the ‘Access to clean cooking alternatives in rural India’ programme, induction stoves were introduced in nearly 4000 rural households in Himachal Pradesh, one of the very highly electrified states in India [4]. (Manjushree Banerjee et al., Energy Policy, 2016).

- The economic indicators of the state in general show better performance when compared to corresponding figures at the all-India level. (Rural average MPCE was USD 29.14 in 2013, as against the all-India average of USD 20.12) [MoSPI, June 2013]

- Analysis of primary usage information from 1000 rural households revealed that electricity majorly replaced LPG (used as the secondary cooking fuel), but did not influence a similar shift from traditional mud stoves (primary cooking technology).

- As of 2023, only in 12 states in India the average monthly household power consumption exceeds the national average of 86 kWh per month (the estimated mean electricity consumption by induction stoves per month is 82 kWh). [This would be a major entry barrier for the mass-level penetration of eCooking appliances. This is more of a consumer behavior-oriented issue coming from lifestyle choices].

- Delhi, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Assam, and Kerala have seen a gradual inclination towards the adoption of electric cooking (eCooking) devices [5]. (CEEW, 2021)

- In Delhi and Tamil Nadu, about 17% of households have adopted some form of electric cooking (in the form of induction cooktops, rice cookers, and microwave ovens), while in Telangana the household level penetration of eCooking stands at 15%.

- CEEW study highlights that the penetration of eCooking among urban households stood at 10.3%, while that for rural households stood at just 2.7%.

- In areas where power supply is available and by and large reliable, specialized electrical appliances such as electric kettles, rice cookers, ovens, and microwaves are used.

- However, these usages are often limited to specific purposes only.

- Electric coil stoves have not been considered a good policy option due to their lower efficiency (~75%) and higher power consumption as compared to state-of-the-art modern devices [6]. (Smith and Sagar, Energy Policy, 2014).

6. A Certain Kind of Transformation is Pre-requisite for Success of Residential eCooking Transition: Personal Reflections

- Debates and discussions largely revolve around health issues associated with traditional ways of cooking (solid biomass burning and IAP).

- In India, health advice does not work until there is a medical emergency.

- Advice works only at the personal level in general, not so much at the community level.

- Therefore, appropriate communication agendas, communication channels, and dissemination experts need to be identified/ developed/ deployed. (A big pool of people from different backgrounds and verticals with efficient coordination and information needs to be formed) Finovista has already made a big contribution, but we need more.

- Although energy efficiencies of various modern eCooking devices are discussed often, more clarity is required regarding the actual electricity consumption and its expected impact on the monthly electricity bills. (People are worried about energy bills – insights from the HH survey conducted by NIAS in Bengaluru).

- Many poor people shifted from solid biomass to LPG, and LPG prices went high. What happens if they shift to eCooking and start bleeding financially? (Concerns captured during Bengaluru Field Survey). The administrative trust factor has to be restored and adequate social protection needs to be ensured.

- Clarity is required amongst the common people regarding the types of vessels that can be used in different eCooking devices.

- Like eCooking appliances, vessel manufacturers should think about price reduction through demand aggregation, or appliance-vessel pairing while offering commercial solutions.

- Dissemination is required in terms of eCooking device safety features. A survey of low-to-medium-income households in Bengaluru indicates that consumers are worried that they will get electrocuted, especially if the water spill happens on the induction cooktops during boiling water or cooking rice.

- Innovative cooking techniques need to be disseminated among the consumers considering the wide range of vessel sizes available in the market. People purchase vessels considering family and serving sizes.

- Appliance manufacturers may also come up with separate device variants for vessel sizes that serve 3-5 people, and those which serve 6-10 people (regional surveys would help firm up the specific requirements).

- Also, double-pan devices can be thought about for small vessel-size appliances. (Families with multiple working individuals would prefer this since it saves time. Well-to-do families with more than one earning member won’t be so worried about the electricity bills.)

- Free electricity may prove to be a tricky facilitator for eCooking devices. Policymakers need to think about whether free electricity can be provided forever. (What about DISCOM’s revenues and Govt’ exchequer?)

- Change has to be more from the fundamental socio-cultural and behavioral side, rather than being incentive and enabler-based.

7. Importance of Community Engagement is Paramount

- eCooking Entrepreneurs alone won’t be able to transform Indian society.

- Often society perceives entrepreneurs negatively, as persuasive ‘selling agents’ of products.

- We need educators (school teachers, college/ university professors, and energy professionals) to work together to chart out a common course on Clean Cooking Education. Another course is required on general Energy-Efficiency Learning. Such courses should be made part of module-based mainstream learning.

- The quality of energy-related magazines and blogs needs to improve substantially. The main focus should be on good content, but attention should also be on the presentation. The visual look of the reading material should not be the same as event management pamphlets.

- We need also doctors and nutritionists in the group to talk about the health benefits of the food made using eCooking appliances. Apart from IAP sensitization, dieticians and nutritionists should sensitize the public regarding the potential health hazards attributable to long-term consumption of some of the traditionally made “tasty food items”.

- Mohalla Cooking Discussion Clubs need to be formed to engage women in cooking-related information sharing and eCooking discussions. Community-level mentors should be identified and provided with training on up-to-date knowledge (a mix of women of various levels of experience is desirable to have the maximum reach).

8. An Essential Consideration for Ensuring Youth Engagement in eCooking

- The author delivered a talk on the theme “Engaging Youth for eCooking” in the Virtual Talk Series Phase III on Transitioning to Modern Energy for Cooking organized by Finovista, in-country partner of the MECS Programme, Loughborough University (UK) in India on December 21st, 2023.

The key takeaway from the talk was –

- Youth engagement would require dignified career opportunities across the clean cooking value chains.

- Youth engagement initiatives should devise an appropriate responsibility portfolio considering different age groups.

- Capacity building should aim to make the youth employable.

- On the other hand, capacity building is needed to absorb the trained talent pool.

- Dissemination of knowledge (energy efficiency, environmental benefits, nutritional benefits associated with eCooking), discussions for spreading awareness, and hands-on training (manufacture, demonstration, servicing, and repairing) would form the core of the “youth engagement” strategy.

9. Concluding Remarks: Personal Reflections

- A large-scale socio-cultural transition such as the ‘shift toward eCooking’ is a process (or a journey) rather than a destination.

- Apart from the business potential it offers, it would potentially create a large number of aware and educated citizens. (Formation of social capital).

- Strengthening appliance and vessel manufacture would reinforce the country’s domestic MSME sector.

- Improved eCooking appliance safety culture would enhance manufacturers’ competitiveness (and also acceptability) globally.

- Through knowledge sharing and coordination ‘social cohesion’ and ‘social networking’ would improve’ (NIAS interns have undergone massive improvements in their communication skills).

- Academic training on energy efficiency, environmental benefits, nutritional benefits associated with eCooking, hands-on training manufacture, demonstration, servicing, and repairing, will lead to large capacity building in the country. [This is important considering the population size of our country. Scaling of initiatives would require more people].

- Formation of efficient public relations channels would help improve the transparency of communication across the whole ecosystem encompassing industry, entrepreneurs, innovators, educators, policymakers, and consumers. (Transparency and cohesion are key to good governance)

References

[1] Faizan, M.A., Thakur, R. (2019) Measuring the impact of household energy consumption on respiratory diseases in India. Glob health res policy 4, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-019-0101-7

[2]Khandelwal, M. et al. (2017) ‘Why Have Improved Cook-stove Initiatives in India Failed?’. World Development.

[3] Basu, A. (16 May 2023) The problem with improved cooking stoves. The Hindu. <Retrieved from: https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/science/improved-cooking-stoves-harmful-ultrafine-particles/article66853734.ece >

[4] Banerjee, M. et al. (2016) Induction stoves as an option for clean cooking in rural India. Energy Policy, Vol. 88, pp. 159-167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2015.10.021

[5] Delhi and Tamil Nadu lead India’s switch to electric cooking with 17% adoption (18 October 2021). Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW). <Retrieved from: https://www.ceew.in/sites/default/files/CEEW-Press-release-Delhi-and-Tamil-Nadu-lead-Indias-switch-to-electric-cooking-with-17-percent-adoption-18Oct21.pdf>

[6] Smith, K.R., Sagar, A. (2014) Making the clean available: Escaping India’s Chulha Trap (Viewpoint). Energy Policy, Vol. 75, pp. 410-414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.09.024

…………………………..

Featured image credit: Finovista.