- Date

- 11th May 2023

- Categories

- Clean Cooking, Electric Cooking

By Dr Simon Batchelor (Gamos Ltd., Loughborough University).

MECS is researching the reach of the supply chain down to the consumers, trying to ensure that all the elements are in place for modern energy cooking services use to become a normalised reality. This blog draws on some research undertaken in health information seeking and draws attention to where households get information about new possibilities, whether that be health, agriculture, livelihoods, purchases, or rights.

So far, we as a MECS research community have tended to focus on the private sector for supplying and retailing appliances. Our research has been on how companies can get their products to potential customers. So, it means we have tended to work with companies and NGOs to develop a supply chain, where their sales are made through their own targeted outreach. Indeed this is the core of our current SC2 challenge fund, Phase 1 of which will deliver the business plans late this month. This approach has been to try to ensure that there is a supply chain that actually lands, assembles or creates the appliances in country and ensures that the option is there for consumers to purchase the product in local currency (i.e., without the consumer having access to foreign exchange).

Through our other challenge funds, there have been a number of ‘pilots’ where households have been invited to use a MECS appliance (e.g. ECO Challenge Fund). Beyond these, to date, the other option for consumers has been to access MECS appliances in some retail stores in the capital or online. Some stores like the Sarit Centre at Westlands, Nairobi, have tentatively offered the wealthier urban household such appliances, mainly at a cash purchase price and by displaying them alongside other trappings of modern society. Supermarkets sometimes offer the appliance in much the same way as Walmart might offer in the USA.

However only certain sectors of society frequent these retail locations. Sometimes word of mouth on how good an appliance is might encourage a foray into these stores, or there have been occasions where the urban household might buy an appliance for a relative, but generally it’s safe to say that retail outlets like these are not going to reach the majority of African consumers.

In the paper consumer journeys, we acknowledge that online purchases are also a pathway for purchasing such appliances, and its use is increasing; indeed one of our partners has made viable strategy through online sales in developing Asia. Consider this example from Nigeria. Online sources depend on solid marketing, whether that be conventional advertising or again ‘word of mouth’ (social media).

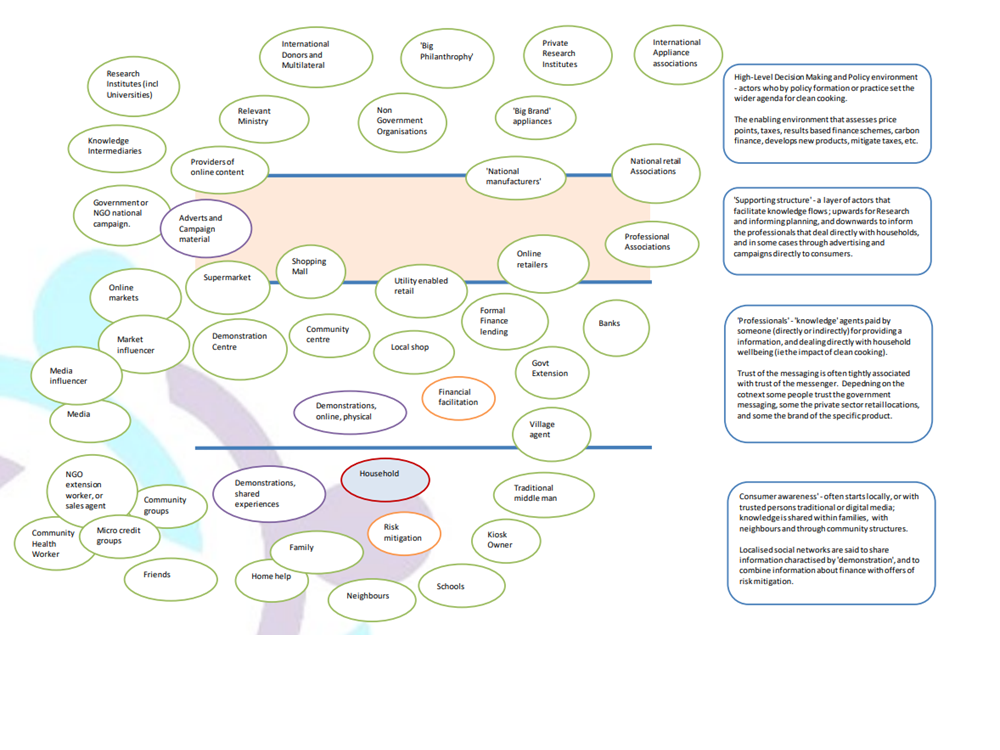

As we move towards a scaled uptake of eCooking appliances, how can we now reach the digitally challenged who live in areas of Africa and Asia who don’t frequent the city much, and wouldn’t go into a retail store? In the consumer journeys paper I built on some research undertaken around health information networks, to map out the possible connections and routes households have for critical information, and identify key actors who might now need to be informed of the new MECS opportunities.

There is of course wide array of possibilities, but we can cluster them to some extent. Almost all communities have health workers and agricultural extension workers. Community health workers are sometimes from the community itself or are professionals who are commissioned by government or NGO to work alongside the community. Extension agents can sometimes be employed by the private sector particularly if there is a cash crop such as coffee or sugar, but also there are salaried generalists paid by government. In some cases, NGO’s have focused on ‘animateurs’, those who seek to socially mobilise the community to solve their own problems, across education, health, livelihoods, resilience, even rights. All these community workers would benefit from knowing that eCooking is affordable, culturally acceptable, beneficial to health, and beneficial to the environment. It won’t be their job to promote eCooking every time they enter a community, but it would be good for them to be aware and realise this new opportunity exists.

Consumers will need finance for the upfront purchase, and while some appliance suppliers are looking to offer a package that spreads the cost, there is also a vast network of microfinance to tap into. At a community level there are often self-help groups, particularly of women coming together to support each other in purchases, but there are also the more formal MFI’s, with their agents discussing and offering opportunities to the consumer. Again, each of these agents and these groups would benefit from knowing about the emerging opportunities for life improvement through modern energy cooking.

In one of the opening paragraphs, I suggested that supermarkets with their array of 20 appliances on a shelf, were unlikely to be frequented by the remote rural dweller. But while this may be true, every community has kiosks and ‘local shops’ that sell things to the community. For some, it may be small packets of rice or sugar, but increasingly, certainly near market towns, there are the providers of larger items. They probably cannot afford to have 20 appliances on the shelf ‘in case’ someone wants it, but if they are properly networked with distributors, they can display the possibilities and then obtain the goods when they are ordered by the consumer. Some may be true ‘middlemen’ who visit the community regularly to both purchase agricultural produce and offer delivery of inputs such as fertiliser. They could promote emerging eCooking possibilities.

Connected with these localised shops and retail, are also the agent networks of the telecoms and the renewable off-grid sector. It has become a vital part of almost all communities that they can refill their airtime on their mobile phone. Airtime sellers have become ubiquitous. There is therefore a strong argument that if we can work with mobile network operators to advertise these new opportunities, and ensure their agents know where to access the appliances, that could be a very strong route to market. Indeed, the original work on health information networks was a part of the GSMA mHealth and mAgri programmes, and showed the importance of timed health and agricultural messaging. In the same way Shamba Shapeup has integrated a segment on eCooking into its wider agricultural programming, so there are possibilities of informing consumers about the new opportunities through strategic messaging too. The off-grid sector also has a good reach into rural areas, with agents being able to explain the benefits of adding eCooking to their emerging suite of energy access. Unfortunately, at the moment most off-grid companies do not yet see a viable price point and are suggesting consumers take up LPG on a PAYG basis, but this will change rapidly over the next two years.

Beyond the private entrepreneur who may be running a local shop or being a travelling sale person for a company or distributors collective, households may also have a community centre as an information resource, a communal place where people meet to share ideas. This possibility brings me to note the importance of demonstrations. Demonstrations are the most convincing mechanism for rural communities. Whether that be a cooking demonstration by a neighbour, showing off a new appliance, or a formal cooking demonstration at the community centre.

So, there are a number of connections households have into society to find information. Each of these provides routes for making households aware of practical emerging opportunities and technologies and in particular for pointing to the emerging possibilities for modern energy cooking. At some point the eCooking cadre needs to insert the information into the flow, and we are rapidly reaching the point where NGO’s particularly those working in livelihoods and resilience, in health and in microfinance, could benefit from a briefing on emerging possibilities. It will also be important for distributor collectives such as GDC and off-grid suppliers to work together to provide an integrated service to the communities.

Featured Infographic: Authors construct based on previous work in Bangladesh on health information seeking. Credit Batchelor 2015