- Date

- 17th May 2022

- Categories

By Nigel Scott (Gamos Ltd.) and Prof. Matthew Leach (Gamos Ltd., University of Surrey).

Over the years, the MECS programme has generated cooking data from multiple countries through various activities. When we have found that the cost of cooking with electricity compares favourably with traditional fuels, we’ve never been sure if that simply reflected some characteristics or context that was unique to the specific country. In order to draw more generalised conclusions, we pulled together data from these multiple sources, and made a start with comparing the energy required to cook individual dishes using different fuels and devices, as well as the associated costs. The analysis presented in a working paper has not only confirmed that cooking with modern energy efficient devices can be cost effective under many conditions, but has also thrown up some interesting findings that illustrate ways in which electric pressure cookers (EPCs) work.

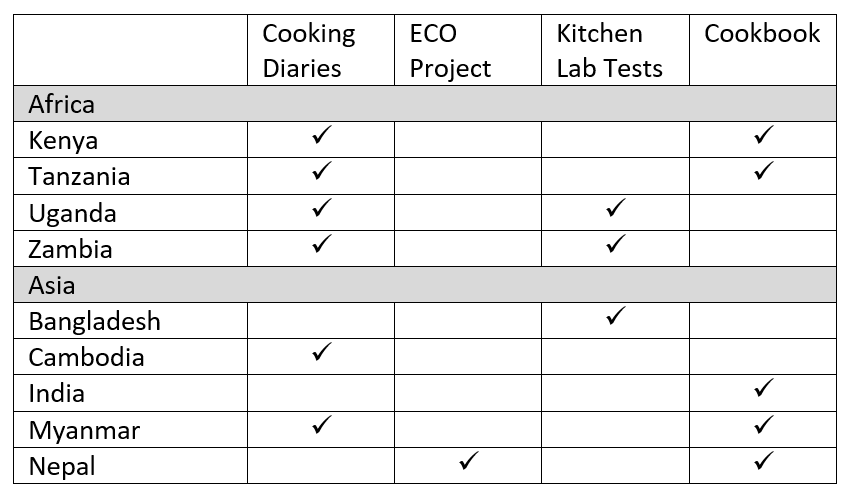

The collated dataset contains over 200 data points for foods cooked using a range of electrical appliances, and over 130 data points of foods cooking using traditional fuels (wood, charcoal and LPG). MECS has been particularly interested in whether cooks can use energy efficient EPCs in their kitchens, so a large proportion of the electric cooking data points relate to EPCs – others relate to a mix of hotplates, rice cookers, microwaves etc. Data has been gathered from the following types of studies across the countries in Table 1:

- Cooking Diaries – a small number of cooks (e.g. 20) are typically asked to cook as normal for a couple of weeks (baseline phase) and then to swap to using electric cooking appliances to cook as much of their menu as possible during a transition phase. During the study, cooks record all the dishes cooked, and measure the energy used (a more detailed description can be found in the Cooking Diaries 3.0 Protocols document).

- The Electric Cooking Outreach (ECO) Challenge Fund – one theme of ECO investigated whether efficient electric cooking appliances fitted the cooking culture and electricity supply, and many of the studies included some kind of cooking diaries exercise. However, only one project, in Nepal, generated data on individual dishes.

- Kitchen lab tests – these take a mixed-methods approach, combining Controlled Cooking Tests (CCTs) with qualitative data that takes account of the cooking experience as well as the quality of the dish from an eating perspective. A small number of typical dishes are cooked by the same cook but using different fuels and appliances. Tests are repeated multiple times for each dish.

- Cookbooks – present data on the energy and cost of cooking a small number of dishes using different fuels. Sometimes data from the kitchen lab tests is used and sometimes data is generated by the cooks who contribute recipes for the cookbook.

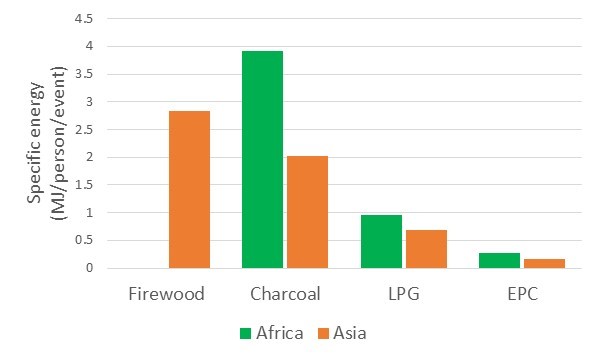

Given differences in diet and cooking style between Africa and Asia, we might expect to see regional differences in energy consumption, and Figure 1 shows exactly that – for all fuels used, African dishes use more energy. This figure also shows that modern fuels use much less energy than biomass fuels. This figure doesn’t show the effects of a small number of popular dishes, all found in Africa, that are especially energy intensive: chicken biryani and matoke from Kenya, and a Zambian bean stew.

The analysis revealed some interesting features of how an EPC works. For example, the data shows that the variation in energy used to cook dishes is much lower when using an EPC. Most of the energy consumed is used in bringing the contents up to pressure. Once at pressure, automated control adds only small amounts of energy to make up for heat lost during the cooking period.

Cooking devices are usually assessed by comparing thermal efficiencies, and protocols are available that describe precisely how this can be measured, such as a water-boiling test. But this doesn’t really work for modern devices that cook food in a different way. For example, the data shows that hotplates use approximately 2.5 times as much energy as EPCs. But the efficiency of a cheap hotplate measured by a water-boiling test might typically be around 60%, which implies that the efficiency of an EPC is 150%, which is nonsense. The problem is that cooking under pressure at an elevated temperature means that cooking takes place quicker, and requires less energy. So asking about the efficiency on an EPC is the wrong question – we should be asking about the energy required to cook using different devices.

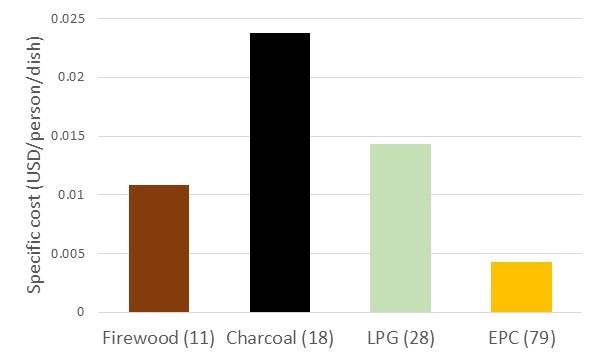

But cost is more important to cooks than energy. Figure 2 indicates that across all dishes captured, the costs are lowest when cooking with an EPC, and highest with charcoal. The cost of cooking with an EPC is approximately one third the cost of using LPG, and less than one fifth of the cost of using charcoal (based on media figures). These figures are based on prices prevailing in the study countries at the time of the study. They include a wide range in electricity prices, from a lifeline tariff in Zambia to the near full cost recovery tariff charged in Uganda.

The conclusions from the overall dataset can be summarised as:

- Cooking individual dishes using an EPC offers substantial cost savings over traditional fuels;

- Using ‘efficiency’ to compare devices is not appropriate for some devices, such as the EPC because the ‘useful’ energy supplied is different to that using traditional cooking methods. A better definition of the ‘useful’ energy to use in an efficiency test is not obvious. Specific energy used to cook a dish or meal, and the energy ratios that come from comparing energy used when cooking with different fuels and stove types, may be helpful.

- Cooking with charcoal uses 15 times as much energy as an EPC; cooking with LPG uses four times the energy used by an EPC.

- Regional differences in cooking styles result in different amounts of energy needed – African dishes used approximately half as much energy again as Asian dishes.

…………………………….

Featured image, top: Electric Pressure Cooker (image credit: CREEC, 2022).